Transcript of a talk by Ankur Barua.

We will consider one of the most polyvalent concepts in Hindu religious worldviews – namely, bhakti. I will focus on one particular set of meanings of the Sanskrit word bhakti – namely, devotional love or loving attachment. One encounters bhakti in diverse contexts of Hindu life – as an attitude of dedication to an icon (mūrti) of the divine reality placed inside a massive temple or a small household shrine; as an expression of joyfulness in congregational singing or seasonal festivals of a deity; as the animating force on pilgrimages to sacred sites; and so on. Thus, bhakti is interwoven with the ritual practices, scriptural cosmologies, spiritual disciplines, and material cultures associated with various Hindu lineages.

On this occasion, I will engage with bhakti with respect to two interrelated themes: one theological and the other aesthetic. First, I will highlight a conceptual problem relating to the nature of God; second, I will indicate how this problem is not so much resolved, in the way that you solve a mathematical problem, but inhabited, in the way that you may wait with hope and patience for a seemingly absent lover.

Let’s begin with one basic question – what is it that theologians do?

Well, they do many things, but here is one basic question they often ask – how do we talk about God? We know that God, by definition, is not a finite object. So, I cannot have a sentence like: “God is a musician from Cambridge”. Indeed, it seems that I can never complete a sentence of the type: “God is ….”

Let’s look at three ways in which Hindu theologians grapple with this problem. The first way says: “multiple as many descriptions as possible for completing this sentence”. In Hinduism sometimes the divine is represented as feminine. In one famous hymn, the Goddess (devī) is said to have 1000 names. In principle, there is no reason why the number stops at 1000 – if you have enough time and energy you can increase this number to 5 billion or 5 trillion. The second way says: “God is so utterly ineffable that this sentence can never be completed. The only way to speak of God, paradoxically, is by saying absolutely nothing”. The third way – the way that we find in many styles of bhakti – says: “take one name and treat it as an analogy”.

This third way has many forms, but I will consider one main form which is centred around the idea of devotional love of God. Here, the central claim is that God is Krishna who is supremely beautiful, so bewitchingly beautiful that gazing at God would make your heart gravitationally drawn to God.

So, why do we need to speak of analogy? Because God’s love is not like my love for my friend which is subject to variation with time and space. So, the word bhakti that I am here translating here as “love” has a wider connotation than our idea of love that may be shaped by Hollywood movies – by love we may mean romantic love, and just that. But bhakti, while it does include romantic love, has a wider spectrum of meanings. Think of bhakti as a cosmic power that draws human beings to their true source, namely, God.

Let’s say your beloved is right now in New Zealand. Now suppose you get an email saying that the beloved is seriously ill. You immediately walk out of this room, buy an airplane ticket, and fly to New Zealand. What would that show? That love is a cosmic power that makes the world go round.

So, by bhakti, we mean the unswerving devotional love that the human self (ātman) should cultivate towards the divine reality (brahman), who is Krishna, the supremely beautiful divine reality. Now, why should ātman cultivate such unswerving devotional love towards brahman? The answer is – “because ātman is existentially dependent on brahman”.

Suppose you are financially dependent on your sister. That may be one good reason to develop a lot of love towards her. Suppose in an alternative universe, you owed your very existence at every moment to your sister. Would not the intensity of your love towards her become magnified a thousandfold, a million times?

This is one reason why bhakti forms of Hinduism often use the language of intimacy when talking about God. Suppose your lover asks you, “How much do you love me?”, and you reply, “My love for you is as high as 8,848 metres”, they may not be very impressed with that remark. However, if you were to say, “My love for you is so deep that I am unable to measure those depths, so intertwined you are with the fabric of my being”, that is a very different language game. Somehow when we speak of love, metaphors of height that evoke majesty are not as suitable as metaphors of depth that evoke intimacy. Now, according to Hindu bhakti traditions, this is because brahman, who is Krishna, is not somewhere out there on the top of Mount Everest – rather, brahman is right here in the innermost depths of your ātman.

To say that God is with you does not mean that God stops being God and loses God’s sovereignty. We find this intertwining of God’s cosmic power and God’s intimate presence in a text called the Nārada Bhakti Sūtras, which gives you a range of meanings and experiences.

Though [bhakti] is one it becomes elevenfold—of the form of (1) the Attachment to the Greatness of the (divine) Qualities; (2) the Attachment to the (divine) Form(s); (3) the Attachment to the (divine) Worship; (4) the Attachment to Remembering (the deity); (5) the Attachment to (divine) Service; (6) the Attachment to the (divine) Companionship; (7) the Attachment of Parental Affection; (8) the Attachment of the Beloved; (9) the Attachment of Self-Offering; (10) the Attachment of being Suffused; (11) the Attachment of the deepest Separation.

If you look at 1., 2., 3., and 5., you sense the emphasis on adoring God, worshipping God, and revering God. Here God is the God above you, away from you, and over you. However, if you look at 7. and 8., you sense the emphasis on the God who is with you, in you, beside you, and next to you. At 7., in particular, God seems to need your love.

Suppose you seek to cultivate bhakti (7), the bhakti of parental affection towards Krishna as an infant. Consider the difference between cultivating bhakti towards your sister when she is a little baby and when she is 45 years old. In the latter case, your bhakti may be filled with expectations such as, “If I love my sister, she will think well of me. In that case, the next time I need some pocket money to go to Brighton for the weekend, I can email her and she will do a bank transfer in fifteen minutes”. But you cannot possibly harbour such expectations when you love your baby sister, because you know that there is no way that a baby can help you with your problems. So, the central claim in bhakti (7) is that it is much easier to cultivate selfless love by loving a baby than by loving a human being who is 45 years old. Thus, in some Hindu temples, you will find women standing in long queues with various types of food which are offered to the image of baby Krishna.

This style of bhakti is highlighted in a famous narrative from a text called the Bhāgavata- purāṇa where Yaśodā tells her infant Krishna that his playmates have complained that he has eaten some earth, and is struck with awe when on peering into his tiny mouth, she sees multiple universes enfolded into its finitude. Yaśodā sees entities such as the sky, the moon and the stars, and so on – along with herself. Bewildered, she decides to surrender herself at his feet, considering him to be her refuge, when Krishna, through his cosmic power, makes her forget the vision, so that she again takes her infant on her lap with maternal affection.

Perhaps the most intriguing form is bhakti (11) – the bhakti of the deepest separation. The claim here is that when you feel that God has deserted you, the agony that you would experience has a spiritual power to purify you.

Let’s see how this idea works by returning to the sister. If my sister lives in the same house as I do, she may become invisible to me. She is just one more person whom I see day in and day out. Let’s say one weekend she flies to New Zealand, and till she lands and sends me a text message, all I do is fret and repeatedly ask myself, “Has she reached?”. In other words, it is precisely her absence that makes her so vividly present to me.

This is an analogy for how the absence of God may have greater power to inflame you with love of God than the presence of God. If God somehow started living with you as your best friend, you may forget to even notice God. However, let’s say that your love for God has reached such a deep intensity that when you feel that God has disappeared for even five seconds, you experience this separation as an unbearable pain.

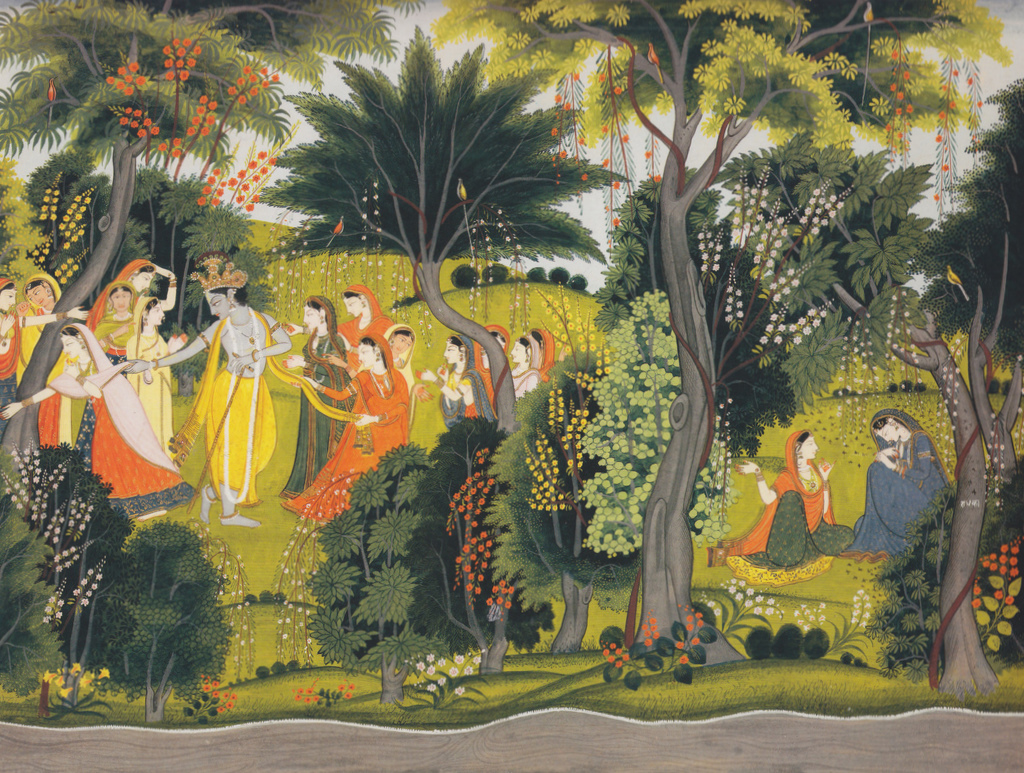

This theme is developed in the Bhāgavata-purāṇa through the paradigmatic narrative of Krishna and the cowherd women (gopī). One evening in autumn, when the charming full moon has risen in the sky, Krishna begins to play on his flute. So enthralling are the notes of the flute that the cowherd women leave behind their domestic chores and run to the middle of the forest to be with him. Some of them become filled with pride in thinking that they possess Krishna, and suddenly Krishna disappears, plunging them into grief. Wracked with pain, they begin to look for Krishna everywhere. This agonized quest, during which they discern vivid signs of Krishna’s absence everywhere, is followed by their reunion with Krishna and their rejoicing when Krishna joins them in a circle dance.

At the heart of these alternations lies the acute pain of separation (viraha) from the divine. In the case of the supreme devotees of Krishna, the more intimately they feel Krishna’s presence, the more painfully they become aware of Krishna’s absence, and the more agonisingly they are torn apart by the pain of Krishna’s absence, the deeper they can move towards the hidden radiance of Krishna’s presence. The supremely personal Krishna engages in a spiralling dance of absence-in-presence and presence-in-absence with the devotees – in modes of divine presence he makes his devotees aware of his infinitude which they cannot humanly grasp, so that they apprehend the divine absence.

While some of the language used in Hindu bhakti contexts is quite distinctive to these contexts, at their heart lies a simple idea which is quite easy to translate across cultural and religious borderlines. The simple idea is this – any labour that you undertake for the object of your beloved is not experienced by you as labour at all. As it so happens, political history is not one of my favourite subjects. If you ask me to write an essay on the Wars of the Roses, I will try to put off writing the essay for as long as I can. And yet when my sister is in hospital, I readily spend five weeks at her bedside, sometimes not sleeping at all throughout the night. So, why is it that I experience the process of writing an essay on the Wars of the Roses as extremely laborious, while I do not even realise that I have spent many sleepless nights at my sister’s bedside? This relatively common experience is what theologians of Hindu bhakti are trying to work with when they say that if you can somehow love God, that love becomes the most effortless labour you will ever undertake.

Now, I am going to present two songs which highlight the theological paradox that it is in and through the seeming absence of God – the dark night of the soul, if you will – that we begin to sense the mysterious presence of God. The first song is from Mādhavadeva, a sixteenth century poet, and a disciple of Śaṅkaradeva, and the second is from Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941). What is common to these songs is that the singer is configured as a feminine or feminized self. That is, the singer adopts or inhabits the persona of a gopī, a cowherd woman, a process that has been given the description “feminization of bhakti”.

In both these songs, you will hear the word ākul or byākul – a deep-seated restlessness in the absence of God – and you will hear the word biraha itself.

The first song starts with the word duḥkha – a concept that is of fundamental significance to Hindu and Buddhist cosmologies.

My friend – how do I express my grief to you?

Not beholding that moon-faced One my soul withers away

O Śyām (Krishna) the embodiment of virtues – through a cruel twist of fate have I lost you!

In the absence of Śyām my life now slips away, my heart yearns to cry out: “Ah, Śyām!”

In the absence of Śyām my life is a tissue of futility, the blazing fire of separation burns away within my heart

In this great despair, Mādhava sings: “My refuge is at the red feet of the Lord!”.

What is particularly interesting about the second song is that the Bengali pronoun সে is ambiguous from a gendered perspective – it can be “he” or “she”. I translate সে as “he” only to situate this song within the Krishna-gopī narrative. Note that there is a reciprocity between Krishna and the gopī – Krishna too is singing a song of separation. Also, note that “Krishna” is not specifically named – Krishna is a symbol of the seemingly distant divine beloved.

I am eager to speak of the matter of my heart – But there is none who would listen to me!

The one to whom I surrendered body-mind-heart did not return Does he wait on me? Does he sing songs of viraha?

Hearing his flute-call I once abandoned my own home.

Cover image: Krishna flirting with the Gopis, to Radhas sorrow. Kangra Painting [Himalayan], c. 1760

Ankur Barua is University Senior Lecturer in Hindu Studies at Cambridge University. He read Theology and Religious Studies at the Faculty of Divinity, Cambridge. His primary research interests are Vedantic Hindu philosophical theology and Indo-Islamic styles of sociality.

One response to “On Bhakti (Devotion)”

Thank you very much for this piece. It heals.

Pronaams, dear Ankur-dada.

LikeLike